A year after taking on one of the US Defense Advanced Projects Agency’s (DARPA) more challenging assignments, Aurora Flight Sciences has frozen the design of the vertical take-off and landing (VTOL) X-plane, which is now designated as the XV-24A LightningStrike.

The XV-24A is a new programme, but Aurora has been quietly working on the technology for nearly two decades. It began with gas-fuelled, ducted-fan-powered unmanned air systems such as Clandestine and the Organic Air Vehicle, which was developed for the US Army's cancelled Future Combat Systems (FCS) programme.

Aurora made the leap from gas-fuelled to hybrid electric propulsion in the wake of the FCS cancellation, launching the Excalibur unmanned air vehicle under a programme funded by the Army Aviation Technology Directorate. Excalibur was powered by a single turbofan and used three battery driven electric lift fans.

To lead the VTOL X-plane project, DARPA selected Ashish Bigai, a veteran of Boeing and Sikorsky rotorcraft, who also was a member of the Collier Trophy-winning design team for Sikorsky's X2 coaxial rotor system.

Bigai adopted a unique approach to developing the design criteria for the VTOL X-plane. Most DARPA projects are conceived to fulfil a particular set of missions. In this case, however, no mission set would be established to dictate the requirements for the aircraft's performance.

"This was conceived as being a little bit of an abstraction," Bigai says. "We took a look at what's been done and what's the art of the possible. Rather than focusing on a particular mission system or mission set, there was a great advantage in pushing technologies to encourage development of new types of design spaces."

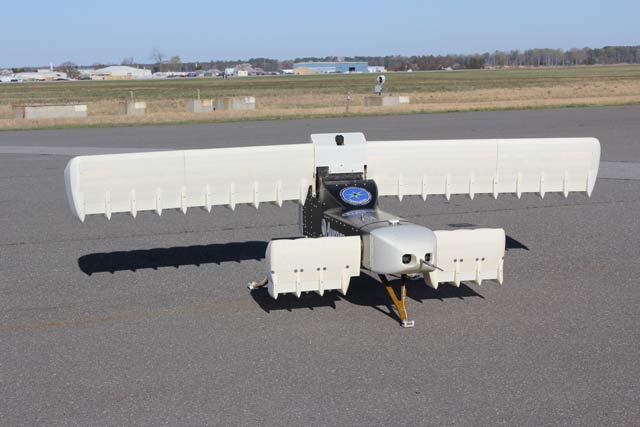

A 20%-scale testbed was was built to prove the innovative concept's power and control systems

Aurora Flight Sciences

The design space DARPA decided to explore was conquering the vast divide between the efficiency of a rotorcraft with vertical take-off and landing capability and the performance a fixed-wing aircraft that requires a runway. So DARPA set the requirements for its VTOL X-plane at the agency's typically strenuous performance levels.

The industry was asked to propose an aircraft with impressive fixed-wing attributes, including a turboprop-like cruise speed of 300-400kt (555-740km/h) and a lift-to-drag ratio of a Cessna 172-like 10:1. Both metrics point to an aircraft with twice the speed and aerodynamic performance of a typical helicopter, yet retaining the rotorcraft's ability to hover and land vertically.

On top of those fixed-wing attributes are two more requirements aimed at creating a respectable helicopter: useful load and hover efficiency.

The useful load is the difference between the maximum gross weight of the aircraft and the combined mass of its fuel and crew. DARPA set the useful load requirement for the VTOL X-plane at 40%. Thus for a 5,440kg (12,000lb)-sized aircraft such as the XV-24A, the useful load must be at least 2,180kg.

Finally, a helicopter's performance is largely defined by the efficiency of its rotor system in hover: a metric referred to as the hover figure of merit. This metric compares the actual energy the rotor system requires to hover against an ideal standard defined by momentum theory. The ideal figure for hover efficiency is 1.0, but most conventional helicopter rotor systems achieve a figure of merit between 0.7 and 0.8. DARPA requires the VTOL X-plane to achieve a hover figure of merit of 0.75, or about the same as a conventional helicopter.

By setting all four requirements – speed, lift-to-drag ratio, useful load and hover figure of merit – DARPA defined a design space that combines capabilities associated with both fixed-wing aircraft and helicopters into the same vehicle. The closest match in an aircraft in service today is the Bell Boeing V-22 tiltrotor, which has a top speed of about 275kt, but with a hover efficiency lower than 0.7 and a useful load of slightly less than 40%.

With testing of the subscale demonstrator and the critical design review of the full-scale aircraft now complete, DARPA is in a better position to judge how well the XV-24A's final design will match up to the agency's lofty requirements. Bigai remains confident the XV-24A will set a new standard for VTOL aircraft performance, even if the aircraft falls short of meeting all four of the agency's design requirements.

"Behind closed doors you can see the performers sweating," Bigai says, referring to the engineering staff in Aurora's industry team for the XV-24A. "Based on how we are proceeding, we may step back a little bit," he adds.

Instead of meeting threshold performance in all four criteria, the XV-24A could make trade-offs. As an example, Bigai cites the option of trading hover efficiency for more speed.

"We could step back on figure of merit to increase speed, while we continue to evolve the programme and refine the technology," Bigai says.

Even if the aircraft falls slightly short of some of DARPA's objectives, the XV-24A would still be an impressive leap in performance.

"I think we'll get very close to [the design requirements]," he says. "I think we'll be significantly better than what we've seen in the past. When we first set up the programme we asked contractors to step out of the zone of comfort and see what other design spaces could materialise given the technology advancements and capabilities. They took that challenge to heart."

The heart of the XV-24A is its unique propulsion system. Rolls-Royce Liberty Works supplies a 6,000shp (4,480kW)-class AE1107C turboshaft, but this is not used to provide thrust. Instead it provides a shaft power output that is used to generate electricity. The engine is linked to a gearbox that drives three 1MW-class electric generators. That energy is then through an electric synchronous control system to drive triple-redundant actuators for the 24 electric fans arrayed along the LightningStrike’s tilting wing and tilting canard.

“One of the cool things about this is that it’s no longer possible to separate propulsion from aerodynamics,” says Aurora chief executive John Langford. “It’s not like you call up your propulsion supplier and say, ‘Hey, I need an engine with this SFC [specific fuel consumption] and this diameter’ and you just strap on your airplane. That is not how this game works. This is totally integrated from the get-go.”

Such an unique propulsion configuration is made possible by several innovations. By necessity, the 3MW bank of generators supplied by Honeywell represents a potential breakthrough in power efficiency. A state-of-the-art generator in the same size class is 90% efficient, meaning the vehicle must manage 300kW of energy as waste heat. By contrast, Honeywell advertises each of the still-untested 1MW generators delivered for the LightningStrike as being 98% efficient, reducing the load of waste heat to 60kW.

Another innovation is the layout of the actuators controlling the 24 electric fans. With a total of 72 actuating devices on board, Aurora has designed the XV-24A with a highly sophisticated control system, with the ability to carefully manipulate the aircraft’s direction and attitude across its full flight envelope. Aurora’s team devised the fans with variable exit area diffusers that can maximise efficiency in hover, then adjust to improve efficiency in forward flight.

Like the V-22, LightningStrike combines vertical take-off and landing with fixed-wing speed, and will fly using Rolls-Royce AE1107C power

US Air Force

“The control allocation strategy for that is not easy,” says Carl Schaefer, Aurora’s programme manager for XV-24A.

The complexity of this unusual power and control architecture drove DARPA to fund Aurora to build a subscale demonstrator, which is essentially an X-plane for an X-plane. Equipped with the full-scale aircraft’s avionics, electric power system and wing/canard fan layout, the 2.7%-scaled demonstrator is intended to discover problems before they appear on the vastly more expensive full-scale aircraft.

The demonstrator completed a total of 10 flights in two phases of testing as of February, Schaefer says. In phase one, the demonstrator cleared parts of the basic envelope, with flights in hover, rearward and sideward movements. The tests also simulated a “lost link” situation, and the aircraft moved to a pre-designated location to hover and land until a control link was re-established. The second phase of testing led the demonstrator to transition from hover mode to forward flight.

More testing of the demonstrator will be required, but the vehicle has out-grown the limits of its test location on the runway at Webster Field in Maryland, Schaefer says. The demonstrator lacks the turboshaft engine component of the XV-24A’s hybrid-electric propulsion system, so is limited to 5min endurance provided by about 55kg of lithium polymer batteries. Even so, the aircraft possesses more capability than it could demonstrate amid the airspace restrictions in Maryland.

“We think it still has some more work to do,” Schaefer says. “It ran out of runway space at Webster Field. We’re looking forward to demonstrating more capability.”

In the meantime, Aurora is assembling an Iron Bird rig to test all elements of the hybrid electric propulsion system for the first time. The rig will include all three 1MW generators, the gearbox and an AE1107C engine. The Iron Bird will operate with these components for several months after its scheduled opening at the end of this year. Simultaneously, Aurora will assemble a sub-scale Copper Bird, which will be dedicated to testing the link from a single 1MW generator to the electric fans in the wings and canard.

The full-scale XV-24A is scheduled to roll out of final assembly at the end of this year, or just as the Iron Bird begins testing. Although structurally complete, the aircraft will be almost empty inside. As Iron Bird testing wraps up next year, the engine and power system components will be integrated into the real aircraft to begin flight testing at NAS Patuxent River in Maryland.

Many questions still linger over the programme. It is rare for a high-performance aircraft to fly with so many thrust-producing fans, each of which can be reconfigured collectively in tilt or individually in pitch. Aurora has analysed the failure modes and mitigated the risk of some, including bird strike. In that case, the danger is that a single damaged fan motor over-torques and damages adjacent fans, turning a small control problem into a much larger one. But the company has inserted provisions in the flight control software to prevent the damaged fan from entering an over-torque condition. The software “knows that something has happened” and compensates, Schaefer says.

The XV-24A has not yet started to take material form as an experimental aircraft, but the possibilities for applying the technology in operations are intriguing. During a 4 April news conference at the Navy League's annual Sea-Air-Space conference near Washington DC, Aurora displayed the aircraft in a configuration similar to the requirements for the US Marine Corps' MUX: a high-speed, shipboard UAS expected to enter service within a decade.

Langford says the most likely first buyer would be a customer with a highly specialised mission demanding a long-endurance VTOL capability, such as a ship-based UAV.

“The XV-15 was a good analogue to what we hope for the XV-24,” Langford says, invoking Bell Helicopter’s proof-of-concept vehicle for a passenger-carrying tiltrotor aircraft. The XV-15 was “not exactly a prototype, but a technology testbed. That paved the way for the V-22 programme. The XV-24 could be a testbed for a future programme – V-27, or something like that. Who knows?”

Bigai takes a longer perspective. The XV-24A matures a suite of technologies that apply to aircraft with electric and hybrid-electric propulsion systems in any configuration. The second-order experience with thermal management of electro-magnetic interference in an aircraft with a 3MW-capacity electric system could also prove useful.

“There’s a lot of firsts here that are taking place,” he notes.

Source: FlightGlobal.com