Boeing remains committed to achieving $50 billion in annual aircraft services revenue by around 2027, part of a broader aim by the company to control more of the commercial aviation ecosystem.

“We did set a big, audacious target,” Boeing chief executive Dennis Muilenburg says during an investor conference hosted by AllianceBernstein on 29 May. “That target has not changed.”

“Admittedly it’s a high-bar target. We think it’s an achievable target,” he adds.

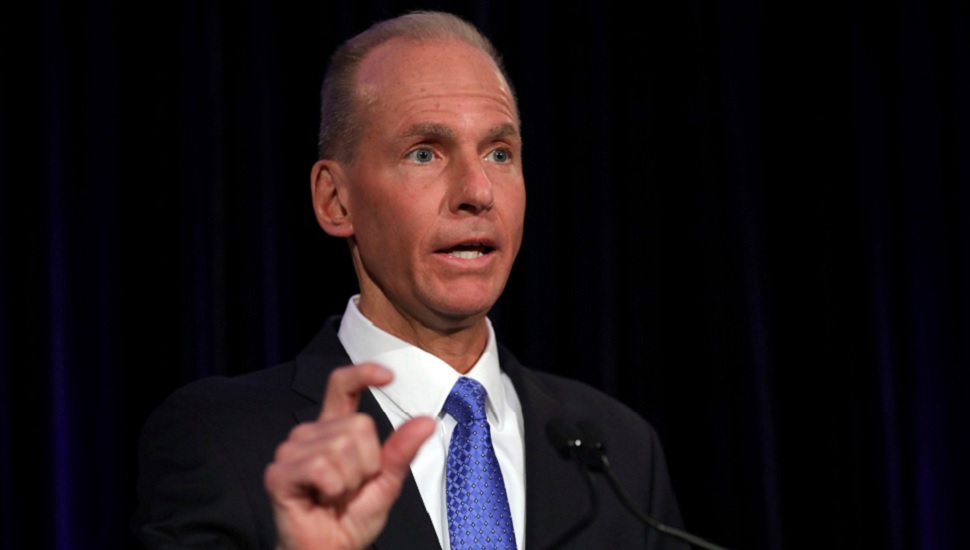

Boeing chief executive Dennis Muilenburg speaks in Chicago on 29 April following Boeing's annual meeting with shareholders

John Gress/AP/REX/Shutterstock

Muilenburg set the $50 billion benchmark in late 2016 when the company merged all its aircraft services work into a new dedicated services unit called Boeing Global Services.

The division generated $17 billion in revenue in 2018, up 17% in one year – gains partly reflecting acquisitions like that of parts supplier KLX Inc.

“We are clearly outperforming the market,” Muilenburg says on 29 May.

The $50 billion mark remains a stretch, but Muilenburg thinks Boeing can sell more products and services related to aircraft maintenance, modifications, parts, training and software – “things that apply to the brains of our airplanes”. He calls Boeing’s services expansion an effort to boost “lifecycle value” – meaning the revenue Boeing can earn over the course of an aircraft’s life.

“Investments to grow the services business will continue to be our primary fuel for growth,” he says. “We do see some opportunity for targeted acquisitions. But I see those as bolt-on complementary acquisitions rather than large-scale acquisitions.”

In March, Boeing acquired ForeFlight, which provides aeronautical data, charts and related software products.

Muilenburg says Boeing’s services growth aligns with its efforts to acquire more of the companies that supply its new aircraft programmes – the business practice known as vertical integration.

Toward that end, in 2018 Boeing formed a joint auxiliary power unit business with Safran and a joint aircraft seating company with Adient Aerospace, and opened a Sheffield, UK factory to make actuators components on 737 and 767 wings. A contractor formerly supplied those components.

Likewise, Boeing has brought in house manufacturing of the 737 Max’s nacelles and the 777X’s composite wings. Those moves shifted away from 737NG nacelle supplier UTC Aerospace Systems (now called Collins Aerospace) and the 787’s composite wing maker Mitsubishi.

Supply chain acquisitions bring Boeing addition services revenue and new expertise that can benefit future aircraft programmes, Muilenburg says.

Source: Cirium Dashboard