French investigators believe inadequate maintenance checks on an Air France Airbus A350-900’s radome led to its collapsing during a turnback to Osaka.

The inquiry found that a bird-strike a month earlier had probably debonded the inner surface of the radome.

But French investigation authority BEA says this surface had not been checked fully during maintenance – despite the skin debonding being sufficient to obstruct weather radar antenna movement three days before the Osaka-Paris flight.

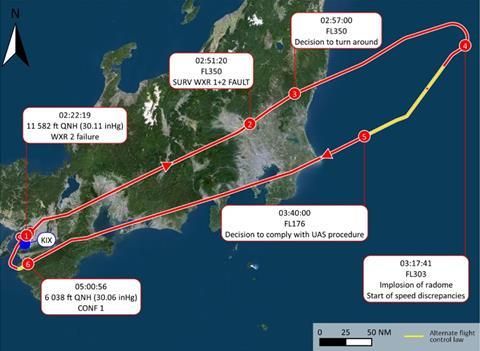

BEA says weather radar faults re-emerged as the A350 climbed out of Osaka on 28 May 2023.

When the faults persisted at 35,000ft the crew opted to return to the airport but, as the jet descended through 30,000ft, the radome collapsed inward.

This structural damage affected airflow and disrupted pressure measurements of the air-data probes on the nose, resulting in discrepancies to airspeed indications and triggering alert messages for air-data problems.

While the aircraft was descending towards 20,000ft the flight-control law switched to ‘alternate’, before reverting to ‘normal’ and then back to ‘alternate’. Further alerts indicated unreliable speed, multiple instances of air-data rejection by the primary computers, and loss of protection under alternate law.

The pilots considered whether the radome was damaged as well as the possibility of a probe malfunction.

They carried out procedures relating to unreliable airspeed, initially leaving the autopilot, autothrust and flight-director engaged. After reviewing the alert messages, the crew observed that ‘normal’ flight-control law had been reinstated.

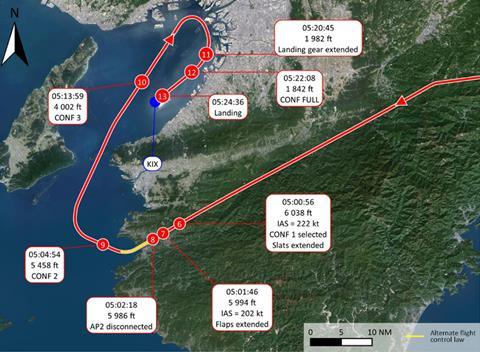

Although an increase in vibration and aerodynamic noise at 15,000ft led the crew to consider diverting to Tokyo, they instead committed to reaching Osaka.

The aircraft was overweight and the crew sought to fly a long downwind leg for runway 24R to prepare for landing.

Another fluctuation to ‘alternate’ and then ‘normal’ law occurred. During the approach, as the slats and flaps were deployed, the crew observed “sudden drops” and “marked differences” between the speeds shown on their primary displays.

“Surprised by this situation, they indicated that they had just lost the radome and that the suddenness of the variations was completely abnormal,” says BEA.

The crew responded by disengaging the autopilot, autothrust, and flight director, and proceed in manual flight – with one pilot using the head-up display while another checked display consistency with the aid of a pitch-thrust data table.

BEA says this decision revealed an “insufficient knowledge” of an air-data protection system that features in the A350.

This system – known as NAIADS, or New Air and Inertia Automatic Data Switching – kept the flight-envelope protection and automatic systems, including the autopilot, autothrust and flight director, available for the duration.

Although NAIADS kept these systems operational, the crew’s disengaging them showed they did not have “detailed” comprehension of its capability, says BEA, a situation which was partly due to an “absence of information” in crew training and Airbus documentation.

NAIADS is designed to automatically supply optimum airspeed data to primary displays and the flight-control laws. It also supplies back-up speed and altitude data independently of the pitot and air-data reference systems, and keeps autopilot and envelope protection available if nullity of air data occurs.

“The crew stated that they were aware of a system that could reconfigure speed sources but that they did not know the details,” says BEA.

It says the system is “complex” and its description in the crew’s flight manual “may be difficult to comprehend in full”, adding: “It is likely that the fragmented and dense nature of the information describing this system does not bring to the fore information of more use to the pilots.”

The crew nevertheless managed to keep the A350 stable during the downwind leg, before turning to intercept the ILS localiser and glideslope for 24R, and landing safely.

None of the 309 passengers and 14 crew members was injured.

“The investigation showed that it would have been possible to make the approach with the automatic systems engaged, as the NAIADS system was functional,” says BEA.

“In less favourable conditions, the strategy of maintaining automated systems remains the preferred one, as it conserves crew resources.”

Airbus updated its maintenance procedures for the radome last year, in the aftermath of the event, to emphasise inspection of the inner surface.

It also revised the A350 flight manual after acknowledging that speed fluctuations, notably during configuration or pitch variations, could prompt pilots to de-activate automatic systems. The revision includes a paragraph specifically referencing the scenario of radome collapse.

Air France has similarly taken steps to tighten radome inspections after bird or hail impact, as well as lightning strikes. The airline has also stressed the importance of recording weather-radar faults, in order to ensure adequate maintenance is performed, and heightened awareness regarding operation of the A350’s NAIADS system.