It began with one man’s vision that the best airplane can only be designed around the best engine. That philosophy of Pratt & Whitney founder Frederick B Rentschler still applies today as the business he established in Hartford, Connecticut celebrates its centennial, and readies, as part of RTX, to power aviation through the next 100 years.

Along with the Wright brothers, Bill Boeing, and Clyde Cessna, Rentschler was a pioneer in an industry that in the early 1920s was fragmented and lacked direction. Powered flight had been around for 20 years, and the First World War had boosted military aviation. But in peacetime the USA and other nations were still pondering what to do with their warplanes and no one – on either side of the Atlantic – had really figured how to make scheduled passenger services profitable.

There were existing engine manufacturers, of course. By 1924, Rentschler – an Ohioan with an engineering degree from Princeton University whose family had a background in the early auto industry – had worked for one of them, Wright, for five years. He had also learned about aircraft engines in the First World War as a lieutenant charged with inspecting military imports from Spain’s Hispano-Suiza.

He became convinced that, with the right team around him, he could dispense with the weight and complexity of liquid-cooled engines by designing a lighter air-cooled, radial engine that would be attractive to both military and commercial aircraft developers. Specifically, he saw an opportunity in the US Navy’s need for a new breed of carrier-borne aircraft and proposed an engine that produced 400 horsepower and weighed no more than 650lbs (295kg).

He won financial backing from several investors, including a machine tool company in Hartford that provided premises and licensed Rentschler its brand – Pratt & Whitney. On 22 July 1925, Pratt & Whitney Aircraft Company was formally incorporated.

![]()

he engine conceived by Rentschler and those who joined him in the company’s earliest days, such as George Mead and Andrew Willgoos, was a breakthrough design that included innovations such as a split rather than solid crankshaft and forged instead of cast crankcases. Within six months of founding the company, the first engine was completed, on Christmas Eve, 1925. During testing, Rentschler recalled that the engine ran “as clean as a hound’s tooth”. His wife Faye, on the other hand, was more struck by the engine’s distinctive buzzing sound, and is said to have inspired the choice of name: the Wasp.

Convinced, the Navy ordered 200 examples of the R-1340 Wasp engine, which soon proved themselves worthy of the company’s “dependable engines” slogan. Thus marked the beginning of Pratt & Whitney’s journey to success.

Scaling up

Underlining Rentschler’s strategy of constant investment and product improvement, a second engine, the 525-horsepower Hornet, was soon underway. The Wasp and Hornet spawned scaled-up variants and over the decades – the Wasp remained in production until 1960 – both engines powered 160 different aircraft types.

The company’s progress did not come without challenges. Pratt & Whitney had broken into the burgeoning commercial sector when Boeing chose the Wasp for its 40-A mail plane, which it operated under its own air transport arm. Several other manufacturers of early airliners also opted for the Wasp and the Hornet, and Pratt & Whitney was on its way to making its mark in this market, too.

However, a deepening Great Depression – which began not long after Pratt & Whitney had combined with the likes of Boeing, Sikorsky, Hamilton Standard, and what was to become United Airlines to form the vertically integrated United Aircraft and Transport Corporation (UA&TC) in 1929 – was impacting demand for air travel. Meanwhile, a US government yet unaware of the threat from Germany and Japan, had slashed military spending, impacting that side of Pratt & Whitney’s business.

Additionally, the Roosevelt administration passed legislation banning operators connected with a maker of aircraft equipment from holding federal mail contracts. It meant UA&TC’s break-up, although its place was taken by United Aircraft Corporation, this time without any airlines or Boeing. UAC, later known as United Technologies Corporation, has continued as Pratt & Whitney’s parent company since 1934, although now under the brand of RTX after the merger with Raytheon in 2020.

The 1930s also saw competition intensifying from the likes of Allison and Wright, clashes between some of Rentschler’s early management colleagues, and financial pressures. It prompted Rentschler to declare that 1937 was the “all-time low” for the business. However, as it did several times over the next nine decades, Pratt & Whitney emerged from turbulent times stronger and more resilient.

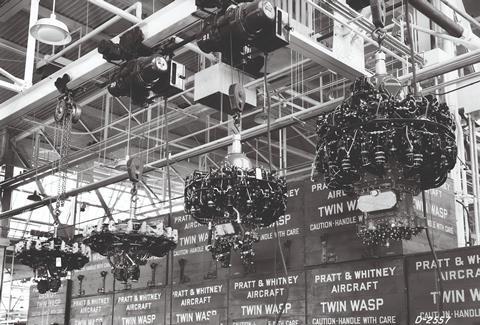

As it did for many aviation companies, the Second World War led to a surge in demand for aircraft and engines, with the business pivoting entirely to the military market. Successful engines like the R-1830 Twin Wasp were fielded for military use, for example on the Douglas C-47 (the military equivalent of the successful DC-3 airliner), the Grumman Wildcat, and the four-engine Consolidated B-24 bomber, of which more than 18,500 were built

Engine production ran into the hundreds of thousands, with new assembly lines at motor companies like Ford, Buick and Continental established to meet demand, in addition to Pratt & Whitney’s own factories in Connecticut and Canada. Throughout the war the Wasp engine design was continually improved to deliver more power and performance, up to 4,000 horsepower, 10 times the original R-1340. As Wasp engines ultimately provided about half of the total horsepower of all Allied aircraft, the company could safely say its technology helped win the war.

However, the surrender of Japan in August 1945 brought new pressures. Almost overnight, Pratt & Whitney’s military business collapsed with its order book falling from $417 million to just $3 million, representing roughly 10 days of production. Ahead, of course, lay the jet age and the start of mass air travel, and the boom years of Cold War military expenditure that spawned supersonic fighters, ultra-long-range, high-altitude aircraft, and the space industry.

However, as 1945 drew to a close things looked bleak, and Pratt & Whitney faced three big decisions. The first was what to do with the sprawling industrial estate the business had been left with at the end of the war. The second was whether the latest evolution of its venerable engine, the 28-cylinder R-4360 Wasp Major, and other piston types had a future. Perhaps the most vital question was could Pratt & Whitney make the leap into gas turbine engines, a technology some of its rivals had begun to work on?

As the engineers of Pratt & Whitney were determined to prove, the piston story was not over yet, with the Wasp Major powering aircraft like the Boeing B-50 Superfortress, which in 1949 became the first aircraft to complete a non-stop round the world flight using aerial refueling. Another application was the mighty Convair B-36 Peacemaker, which exemplified a brief trend toward hybrid-piston-jet powered aircraft, with its six radial engines supplemented by four turbojets – a harbinger of things to come.

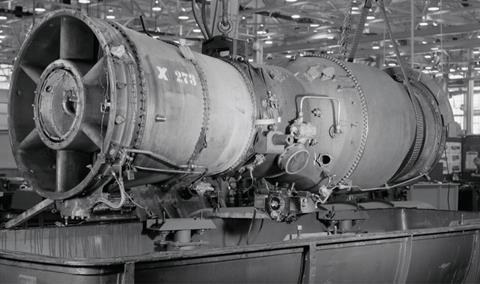

Such had been the importance of radial engine production during the war, that Pratt & Whitney had been prohibited by the US government from pursuing the emerging frontier of gas turbine technology. As a result, the company’s first venture into the jet turbine market was the J42, a derivative of a licensed Rolls-Royce design that the Navy wanted produced in the USA for its Grumman F9F Panther. The Pratt & Whitney designed T34 for the Douglas C-133 cargo aircraft was an early turboprop.

However, the big breakthrough in gas turbines came with the J57, an axial-flow, twin-spool turbojet, which was the country’s first 10,000lb-thrust class engine. It saw Pratt & Whitney leapfrog its competitors at a stroke.

One of the key people behind the J57 was Leonard (Luke) Hobbs, whose contribution was recognized with the award of the prestigious Collier Trophy. Hobbs, who had joined the company in 1927 and led the development of radial engines through the war years, represented a generation of engineers who, like Rentschler and others, straddled both the dawn of aviation and the leap into the jet age.

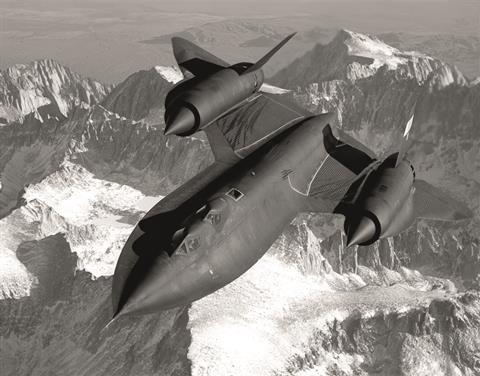

The engine went on to power 13 military applications from the Boeing B-52 to the McDonnell F-101, and its commercial derivative, the JT3, helped usher in a new era for passenger travel with aircraft such as the Boeing 707 and Douglas DC-8. The pace of technology development in this period was rapid, as by the end of the 1950s, Pratt & Whitney was building the J58 for the Mach 3-capable Lockheed SR-71 – an aircraft that still holds the altitude record for a manned flight at 85,000ft.

By the 1960s and 1970s, Pratt & Whitney was producing the likes of the TF30, the first afterburning turbofan, powering the Grumman F-14 Tomcat and General Dynamics (now Lockheed Martin) F-111 Aardvark. Experience from this engine helped inform the creation of the F100, designed for the McDonnell Douglas (now Boeing) F-15 and the General Dynamics (now Lockheed Martin) F-16, two of the era’s most advanced fighter jets.

The F100, which is still in production today, delivered a game changing thrust to weight ratio of eight and was the first engine to feature digital electronic engine control and advanced materials like single crystal alloys; technologies which have since become fundamental across many military and commercial designs.

While Pratt & Whitney had become the undisputed champion in engines for US fighters, the 1980s provided a wake-up call when General Electric’s rival F110 was chosen by the US Air Force as a second engine for the F-16. It led to Pratt & Whitney putting even more emphasis on looking after its number one customer, the US military, and redoubling its efforts in technological development.

One result was the F119 for the Lockheed Martin F-22 Raptor stealth fighter, which went into service in 2005, with a total of 183 aircraft produced. It was Pratt & Whitney’s first fifth-generation engine, packed with innovations such as vectoring nozzles and changes to the engine’s signature to increase the aircraft’s stealth qualities. With two engines generating more than 70,000lbs of thrust, it can also operate supersonically without use of an afterburner, a capability known as “supercruise”.

Shortly after came an arguably even more significant military engine: the F135 for the Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II. Effectively three engines in one – with conventional, short-take off/vertical landing, and carrier variants of the aircraft – there are now more than 1,300 engines in service with 20 countries worldwide. The F135 – which will be modernized with the F135 Engine Core Upgrade (ECU) to deliver additional power and thermal management capacity – surpassed one million flight hours in March 2025.

In parallel, Pratt & Whitney’s commercial business really began taking off in the decades after the war, with the JT3D, Pratt & Whitney’s first commercial turbofan in 1958, followed by the JT8D – which powered the Boeing 727, 737 and McDonnell Douglas DC-9 and MD-80 – and the high-bypass JT9D, chosen for the Boeing 747 and thus playing a key role in making long haul air travel accessible and affordable for millions of people for the first time.

The 1980s saw two crucial developments. Firstly, the launch of the PW4000 as a successor to the JT9D. It was selected to power widebodies from the Boeing 777, 747, MD-11 and 767 to the Airbus A310, A300 and A330. Secondly, the V2500 helped shape the modern-day narrowbody segment by powering aircraft such as the new Airbus A320 family and McDonnell Douglas MD-90. The V2500 was developed through a new joint venture entity, International Aero Engines, comprising Pratt & Whitney, Rolls-Royce, MTU Aero Engines, Japanese Aero Engine Corporation and others.

Although 1996 marked the formation of a joint venture with General Electric to develop an engine for the Airbus A380, the Engine Alliance GP7000, the success of the V2500 and intense competition in the widebody sector saw Pratt & Whitney by the turn of the century consolidate its focus to narrowbodies. And it was into this segment in the 2000s that it unveiled one of the most significant engines in its history: the Geared Turbofan (GTF).

Revolutionary design

The GTF – the first large commercial engine to use geared turbofan technology, in which the fan is decoupled from the low-pressure turbine – enabled a revolutionary 16% increase in fuel efficiency versus previous designs, as well as drastic reductions in noise and NOx emissions.

The engine was chosen exclusively for the clean-sheet Mitsubishi Regional Jet (later Space Jet) and Bombardier CSeries (now the Airbus A220), as well as Embraer’s successor to its ERJ regional jet family, the E2. Most significantly, in terms of volumes, it spurred a wider effort to re-engine existing single-aisle aircraft and was selected as one of two engines available on the Airbus A320neo family.

Pratt & Whitney’s century has also involved forays into the space sector, when in the early 1960s the RL10 became the first liquid hydrogen-fueled engine used in the space missions, including the Saturn 1 launches at the start of the lunar programme. The Centaur upper stage, which has been used extensively on satellite placement and interplanetary missions, is also powered by the RL10.

Meanwhile, Pratt & Whitney Canada – originally created to service then assemble Wasp engines – went on to become the preeminent engine manufacturer in general aviation, with the iconic PT6 engine. The turboprop was the first product developed by the Quebec-based business, entering service in the 1960s and continuing to power dozens of aircraft types in production today.

The Canadian arm has also become a major player in regional aviation (with the PW100 engine family), helicopter engines, auxiliary power units and business aviation with a family of engines from the PW600 for very light jets to the PW800, which shares many technologies with the GTF, for heavier applications such as the G400, G500 and G600 from Gulfstream and Dassault’s Falcon 6X. There is much more on Pratt & Whitney Canada’s origins and successes elsewhere in this special publication.

With Pratt & Whitney enjoying a leadership position in so many areas of the market and quickly developing advanced technologies that equip it for the future, Rentschler – who passed away in 1956, just a quarter of the way through Pratt & Whitney’s first centennial – would have been delighted to know that his company’s obsession with meeting customer needs, delivering quality engines, and constantly innovating is as true today as it was in 1925.

Pratt & Whitney at 100

To mark the centenary of Pratt & Whitney, FlightGlobal has partnered with RTX to produce a souvenir special looking at the legacy and future of one of the industry’s most powerful and influential brands.

- 1

- 2

- 3

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

Pratt & Whitney at 100: Making history – a century of innovation

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13