US investigators have determined that a Bombardier Challenger 605 first officer’s attempt to rescue an unstable approach, after a series of crew lapses, caused the executive jet to stall and roll into a rapid fatal descent.

The crew had been attempting a circle-to-land approach to runway 11 at California’s Truckee airport, having opted against an approach to the shorter runway 20 owing to the aircraft’s weight.

But the crew – arriving from Coeur d’Alene airport in Idaho on 26 July 2021 – failed to carry out a briefing for the new approach, says the US National Transportation Safety Board.

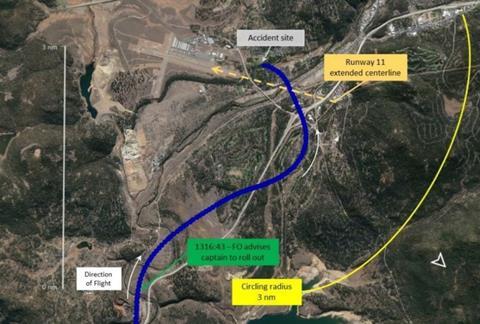

The circle-to-land involved following the runway 20 approach, then breaking off to the right to follow a 3nm radius left-hand arc from which to intercept the runway 11 approach.

Investigators state that the captain was flying the aircraft. But the first officer had already intervened earlier in the approach, because the captain was late in complying with a holding instruction from air traffic control.

The first officer had also remarked that the jet’s airspeed was high, prior to the right turn for the arc, and suggested an orbit to reduce it. But the captain declined the suggestion and never acknowledged the excessive airspeed.

Analysis of the approach found that the captain began the right turn to follow the arc, but stopped the turn prematurely – about 57° before reaching the necessary heading – after the first officer called, “Roll out”.

This meant the aircraft would require an “unnecessarily tight” left-hand turn radius to line up with runway 11, says the inquiry.

As the jet was still flying at 162kt, far above the 118kt reference airspeed, the first officer told the captain he would bring the speed under control, and reduced thrust.

Cockpit-voice recorder information indicates that the first officer was continuously reassuring and instructing the captain during the circle-to-land section of the approach, repeatedly stating that there was no time pressure.

“Patience, patience, patience – you got all the time in the world,” he said at one point. “We don’t wanna be on the news.”

The captain had difficulty identifying the runway, possibly as a result of reduced visibility from smoke in the area, and the first officer repeatedly attempted to point it out before the captain saw it.

According to the cockpit-voice recording, the first officer started to ask the captain for control of the aircraft, stating: “Let me see the airplane for a second.”

The inquiry says there was no formal verbalisation to transfer control, and that it “could not determine” who was flying the aircraft.

But owing to the failure to follow the circle-to-land arc, the jet was unable to make the tight left turn in time, and the first officer realised it would cross the extended centreline of runway 11 just 0.8nm from the threshold.

“We’re gonna go through it and come back, OK?” he told the captain. This suggests the first officer intended to try salvaging the approach despite the misalignment and his recognition that the aircraft was also too high, nearly 500ft above ground.

One of the pilots fully deployed the spoilers, probably to increase sink rate. The airspeed was still excessive, at 135kt, and the aircraft steepened its bank to the left in order to regain the centreline.

Aerodynamic analysis revealed that the spoiler deployment had a “significant effect” on the aircraft’s stall margin during this turn, causing the stick-shaker to activate as the bank reached 36°, says the inquiry.

Had the spoilers been stowed, the stick-shaker would not have engaged until the bank reached 50°.

The crew received ‘sink rate’ and ‘pull up’ alerts, as well as the stall warnings.

“What are you doing?” the captain asked, while the first officer, several times, said: “Let me have the airplane.”

The aircraft, having suffered an asymmetric stall of the left wing, rolled into a rapid nose-down descent and – just 7s after the stick-shaker initially activated – struck the ground about 800m short of the threshold and 300m to the right of the extended centreline.

None of the six occupants, including four passengers, survived. Post-impact fire destroyed the wreckage.

According to the inquiry the first officer was more experienced, with considerably more total time than the captain, including 4,410h on type compared with the captain’s 235h.

The inquiry highlights the first officer’s reassurances to the captain during the approach, even though the fast and tight circling manoeuvre forced a time constraint on the crew.

“These reassurances demonstrated that the [first officer] was aware of the adverse effects of self-induced pressure to perform,” it states, but adds that he nevertheless demonstrated his own self-induced pressure by trying to rescue the deteriorating approach.

Similarly the captain indicated a self-induced pressure to perform, without being corrected, even though there was no urgency to make an immediate landing.

“Once the approach became unstabilised, the crew should have abandoned the approach and gone around but did not,” says the inquiry. “The flight crew’s choice to continue the unstabilised approach rather than go around was consistent with self-induced pressure to perform and degraded decision-making.”

It adds that circle-to-land approaches can be “riskier” than other types, because they often require manoeuvring the aircraft at low altitude and low airspeed during the final segments, increasing the possibility of loss-of-control or terrain collision.