Swedish investigators are closely examining elevator trim settings, and weight and balance calculations, as part of the inquiry into a fatal De Havilland Canada DHC-2 crash during a parachute drop.

None of the nine occupants – a pilot and eight parachutists – survived after the single-engined aircraft, which had climbed to about 400-500ft after take-off from Orebro, entered a 180° left turn before pitching about 45° nose down and descending steeply towards the ground.

On impact, the landing-gear sheared off and the DHC-2 skidded about 50m on its fuselage underside, losing its right wing and burning as it came to rest.

No cockpit-voice or flight-data recorder was fitted to the aircraft, a 1966 airframe registered SE-KKD.

Swedish investigation authority SHK says the flight, on 8 July last year, was the pilot’s seventh parachute lift of the day, while another pilot had performed five lifts.

SHK’s preliminary analysis indicates the aircraft’s vertical climb profile on its final flight was significantly steeper than those of the previous flights. Examination of lamps on the aircraft also found evidence that the stall-warning light had been illuminated before the crash.

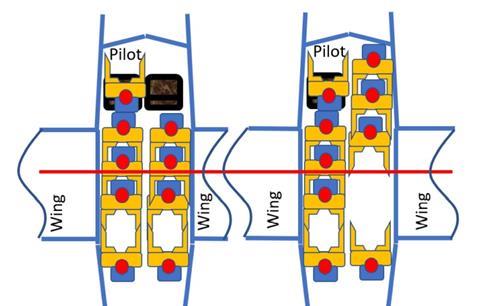

The inquiry says the parachute club which usually used the aircraft had a spreadsheet for mass and balance calculations. These calculations assumed that the DHC-2’s right-hand pilot seat was removed in order to fit two parachutists in the empty forward space.

But the information in the spreadsheet was “unknown” to the pilots flying the aircraft on the date of the accident, and the aircraft still had the pilot seat installed.

This means the parachutists, unable to wait next to the pilot, were sat further back in the aircraft.

SHK says it has “not found” any documented mass and balance calculations carried out before the flight.

The inquiry has tried to construct a detailed model of the aircraft’s weight and balance position, and all calculations have so far indicated that it was near the upper aft corner limit of the envelope.

“It is crucial that the mass and balance of an aircraft are within permissible values to ensure a safe flight,” says SHK, although it adds that being slightly outside this limit does not necessarily mean the aircraft becomes impossible to control.

But it stresses that the aircraft will be less stable, and more sensitive to other disturbances such as incorrect trim settings.

Images from the cockpit wreckage appear to show the aircraft’s elevator trim was set to a ‘nose up’ position normally used to land with only a pilot – and no parachutists – on board, whereas a more neutral setting would normally be used for a take-off with eight parachutists.

SHK has yet to reach formal conclusions about the accident, and is assessing information from other sources including mobile phones, watches and cameras. Acoustic data from the propeller has been examined, but the preliminary findings indicate the engine was producing high power, with positive thrust on the propeller, at impact.