There is something of the tech entrepreneur, or possibly a successful motivational speaker, about Leonardo chief executive Roberto Cingolani.

For one, there is the absence of the typical Italian CEO’s uniform – tailored Armani suit, crisp white shirt and neatly knotted tie – replaced by jeans, a dark blue shirt, jacket and, heaven forefend, black Sketchers trainers.

The radio mic and a shape-shifting red and black backdrop – atoms, apparently – add to the sense of viewing a TED talk rather than the presentation of something as potentialy staid as a five-year industrial plan.

But as he outlined the Italian aerospace and defence giant’s strategy at an event in Rome on 12 March there was a sense that things might be very different under his stewardship.

Cingolani, as he reminds his audience several times, is a physicist by training: “I was a scientist for most of my life and I need formulas from time to time,” he says, explaining how Leonardo’s future financial performance has been calculated.

However, his presentation style and the conviction with which he delivers the message are those of the politician he later became, serving as minister for ecological transition from 2021 to 2022 in the government of Mario Draghi.

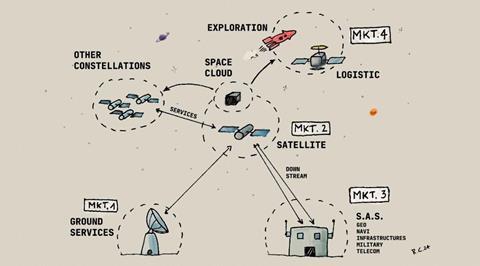

There is also a more playful side: he admits a love for drawing comics and says he sketched out one graphic – initialed and dated ‘RC 2024’ – to illustrate Leonardo’s ambitions in the space sector over the preceding days, finishing off during a board meeting the day before. “My nature comes out here,” he says.

Despite the levity, Cingolani’s strategy is deadly serious. Pointing to the near-60 conflicts raging across the planet – including on Europe’s doorstep – he outlines a changed environment where “security” rather than “defence” is the watchword.

Under the heading “Technologies for a Safer Future”, the industrial plan outlines how Leonardo will “transform into a global, technology-based aerospace and defence solutions provider”.

Through that transformation, it hopes to capture an increased share of defence spending by European NATO nations – forecast to rise by 4.5% to €380 billion ($415 billion) annually by 2028 – pushing revenue to €21.3 billion from €15.3 billion in 2023 and EBITA from €1.3 billion to €2.5 billion.

The three core business units – defence electronics, helicopters and aircraft – will be strengthened, while the aerostructures unit continues its slow recovery towards break-even.

In addition, Leonardo will place increased emphasis on growing its capabilities in the cyber and space fields, establishing a dedicated division for the latter.

All of this is underpinned by heavy investments in high-powered computing – a process kicked off in 2019 during Cingolani’s previous stint at the company as chief technology and innovation officer – and artificial intelligence. Efficiency measures across the group will also deliver savings of around €1.5 billion over the five years.

For the three main “hardware” divsions – the successors to a swathe of storied aerospace brands like Aeritalia, Alenia, Agusta, Macchi, Marconi and Westland – the goal is to become leaders in their respective fields.

“We have to strengthen our core businesses. Our platforms, whatever hardware we make, have to be competitive,” he adds.

In the short-term there is a focus on securing orders for current progammes like the Eurofighter Typhoon – “it has a long tail, it is not something that will be extinguished in the next two years”, says Cingolani – or AW-family helicopters, while in the longer term preparing the ground for next-generation aircraft.

For instance, the helicopter business will “boost tiltrotor [technology]”, an ambition aided by a recent pact with Bell and the ongoing certification of the AW609 which will be “the first building block towards [Leonardo’s] fast rotorcraft positioning”.

Product rationalisation will also take place. That process is already under way in the defence electronics business where around 20% of the unit’s catalogue, chiefly older products, will be cut.

It is not yet clear whether the axe will also fall on platforms in other divisions. But a footnote to a graphic showing its helicopter portfolio says: “For AW119, AW109, AW159/Super Lynx a form of value management will be attempted, finding a suitable partner/buyer.” However, Leonardo did not immediately clarify the strategy for these products.

The only unit where significant change is not foreseen is in aerostructures, where stabilisation seems to be the main goal. Break-even is still targeted for late 2025 and beyond that the aim is to “scale-up to achieve strategic relevance”. Industrial partnerships are also envisaged.

Even if, as forecast, revenues more than double to €1.4 billion by 2028, it will remain Leonardo’s smallest ‘hardware’ business and will be in danger of being outstripped by the emerging cyber and space operations.

Cingolani points out that the business “invested at the worst possible time” – during the Covid-19 pandemic – to improve quality and efficiency and has been fighting to see a return since. But “now we are back to seeing light out of the tunnel”, he adds.

He also sees an advantage in the division’s relative stability, especially when compared to the turmoil seen elsewhere in the sector.

“At the moment our quality is outstanding. You know there are problems in aerostructures manufacturing elsewhere in the world – I think we can guarantee quite an advanced standard,” he says.

The overall business transformation is supported by “massive digitalisation”, with that digital backbone seen as a way of securing additional high-margin services and support work.

Cingolani points to the achievements in the helicopter unit “where something like 40% of revenues are from services because they are ahead in digitalisation”. That 40% figure “should be an achievable target for most of the hardware platforms”, he notes.

International alliances will also be vital, says Cingolani. Leonardo is already involved in the tri-national Global Combat Air Programme as Italy’s industrial representative, alongside the UK’s BAE Systems and Japan’s Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, and he sees more of the same in future, driven by the evolving global context.

Or, as the industrial plan puts it: “Defence is no longer regarding individual national borders but has become an international and ‘global security’ scenario, and the strategy of alliances is one of the possible answers.

“The group will play a proactive role in the evolution of the European defence industry.”

That last element is key: Cingolani points out that “no single European country can make it on its own”, particularly when the continent’s defence industry “has fragmented”.

“Every country in Europe wants its own aircraft, its own tank, its own machine,” he says. “This is not effective, this is not efficient – we have to do much better.”

On this point, Cingolani suggests that there needs to be a change in Europe’s attitude towards mergers and acquisitions to better reflect what he calls the current “war economy”.

The anti-trust legislation governing M&A activity works during “an economy of peace” and “guarantees market competitiveness” which is “good for all citizens”, he says.

“But in the case of wartime you need to understand what the priority is for citizens. Do they still want a free market while the system is falling apart or access to Continental safety? I think safety prevails.”

Meanwhile, Leonardo due diligence is ongoing for up to a dozen bolt-on acquisitions, with these likely to be in the “emerging markets” of cyber, space or unmanned systems. However, the guiding principle is that these must not be more than 15-20% of a division’s turnover, he adds, to ensure they can be easily integrated.

Being Leonardo’s chief executive is a highly political role: the post-holder is nominated by the Italian government, and in practice requires the sure-footedness to balance national industrial policy against market-driven concerns. Given all this, you cannot help but wonder if Cingolani might be tempted by a return to the political arena.

But he is quick to dismiss such suggestions: “I’ve done my civil service,” he says. “I like screws and bolts better.”