Rolls-Royce took more than two decades to get an engine onto an Airbus product. But the UK company is now in pole position as Toulouse’s prime widebody engine partner after securing its third Airbus sole-source supply deal, to power the A330neo.

In truth, Rolls had been part of the Toulouse scene since the late 1980s through the International Aero Engines consortium which began powering the A320 in 1989. But it was the widebody market where it needed to be – and nearly was, right at the start of the Airbus project.

It is ironic that it took Derby so long to get one of its gas turbines bolted to an Airbus, given that the original “A-300” was to have Rolls-Royce power when proposed in the 1960s. The engine was the 54,000-58,000lb thrust RB.207 and the aircraft was a widebody twinjet ancestor of what would become the first Airbus.

Flight International wrote in November 1967: “The next six months will be critical for the Anglo-French-German A-300 Airbus, and indeed, for the European aircraft industry’s aspiration to stay in the front rank of civil aviation. If the A-300 does not secure the necessary 75 orders from the home market for which it has been designed, then Europe may never again build a big transport aircraft – and the world demand will ultimately be met by America and Russia.”

History shows that Airbus got there in the end, but initially it was a Franco-German affair. The UK bailed out of Airbus as a full partner in April 1969 and the “big twin” plans were scaled down around the smaller A300B, spelling the end for the too-powerful RB.207. Meanwhile, Rolls-Royce’s smaller “big fan” – the RB211 – was in development as the sole choice on the Lockheed TriStar. From 1977 it found its way onto the Boeing 747.

Despite overtures from Derby about the RB211, Airbus opted for an off-the-shelf solution from General Electric, so it was the McDonnell Douglas DC-10’s CF6 that powered the first A300Bs. And so began a transatlantic romance that lasted for three decades. In fact, the moment the love affair began to sour can be pinpointed to February 1997, when GE walked away from plans to power the then proposed A340-500/600.

GE blamed the failure of the talks on the two sides’ “inability to agree on financial terms and conditions. We defined the engine for the aircraft’s technical requirements, but could not reach agreement on price and risk-sharing.”

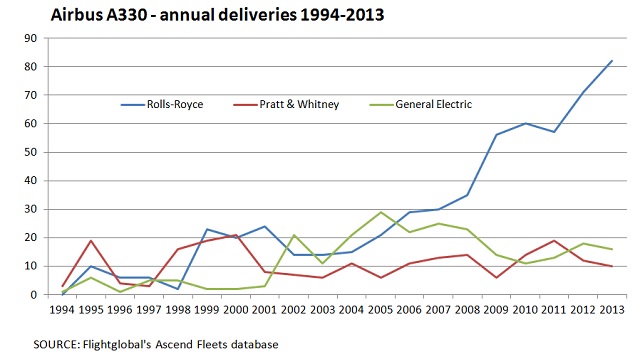

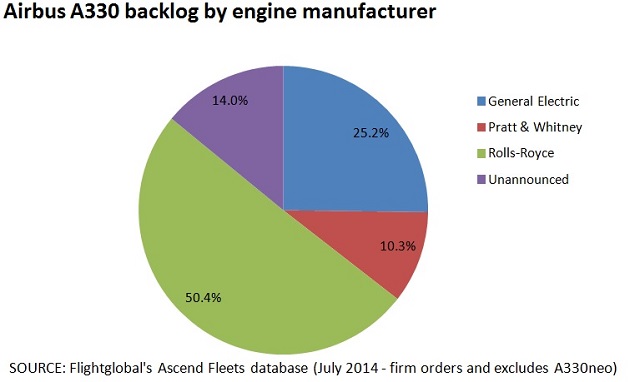

By that time, Rolls finally had its foot in the Airbus door, with the Trent – itself an RB211 iteration – having joined the A330 programme in 1995 as the third of three power choices behind GE and Pratt & Whitney. The first Trent-powered A330 was delivered to Cathay Pacific in early 1995 and today more than 600 of the twinjets are flying with Rolls-Royce power, accounting for more than 55% of the total fleet. Half the A330s on order today (excluding the Neo), will be Trent-powered.

Rolls may have been the new kid on the block in Toulouse 20 years ago, but it quickly charmed Airbus and the Trent became the natural substitute after GE withdrew from the A340-500/600. At the Paris air show in June 1997, Airbus launched the A340 growth derivatives with Trent 500 power only – but avoided describing the deal as exclusive.

The next piece of the jigsaw came in July 1999, when GE signed up with Boeing to be exclusive supplier on Boeing’s “777X” family which subsequently became the -200LR/300ER. With the market estimated at “around 500 aircraft”, Boeing said “the business case didn’t allow us to do anything else” other than a sole-source engine deal.

That argument obviously didn’t stack up for the 787, so Rolls secured a slot on that programme. But the Trent 1000 has struggled to match the success of GE and currently has just a third of the engine market.

When Airbus launched the A350 Mark 1 in 2005, it was powered by a GE GEnx engine. But a Trent option was quickly added and the Rolls option became the only choice a year later when the A330-derived plans were shelved and replaced by the all-new A350 XWB.

The polarising of the GE/Boeing and Rolls/Airbus relationships took another step forward when the US engine maker became sole source on the 21st century iteration of the 777X last year. It had already secured a similar deal on the revamped 747-8 family, although sales in the large-aircraft sector continue to disappoint.

Fast forward to this year’s Farnborough and the final piece of the jigsaw slotted into place, when Rolls and Airbus announced they were getting together to reinvent the A350 Mark 1. And as with all exclusive deals, the customers aren’t exactly ecstatic, but Air Lease boss Steve Udvar-Hazy thinks it will be okay.

Air Lease had been “campaigning for two engine choices”, says Hazy, but after GE absconded, Rolls and Airbus “were able to forge an arrangement that is very satisfactory to the customer”.

Airbus sales chief John Leahy explains: “We have built into the price of the airplane an economic package from Rolls-Royce. We’ve taken the liberty of negotiating [the discount achieved through an engine competition] in advance with Rolls, so all the customers get a good price.”

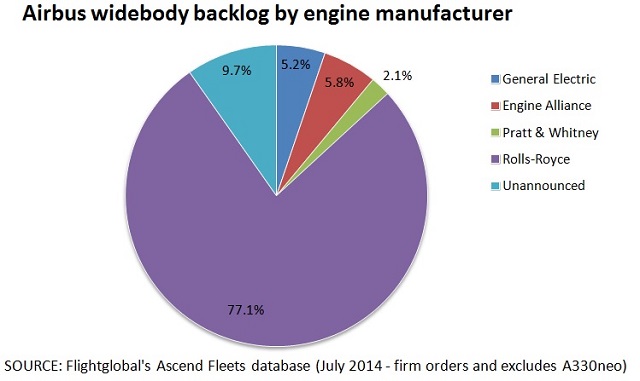

Flightglobal’s Ascend Fleets database shows that Rolls-powered aircraft now account for two-thirds of Airbus’s widebody deliveries each year and almost 80% of its widebody backlog. With P&W in rapid decline and GE taking its ball home on the A330neo, the only non-Rolls position going forward is with Engine Alliance on the A380.

But the next chapter in the Rolls/Airbus love affair may take a little longer to write. With Engine Alliance apparently lukewarm towards Emirates boss Tim Clark’s enthusiasm for an “A380neo”, we could well see a Trent derivative become the exclusive engine on any second-generation Airbus superjumbo.

And as Airbus chief executive Fabrice Bregier said of a re-engined A380 at Airbus’s Farnborough wrap-up conference: “Will it take place one day? Yes. Will it be for 2020? I don’t think so.”

Source: Cirium Dashboard