The Trump administration may (or may not) be considering blocking the sale of CFM International Leap-1C engines and other technology for the developmental Comac C919.

A Wall Street Journal report on 16 February surprised the aerospace community, with sources telling the newspaper that the administration was contemplating not approving GE Aviation’s export licence for the engines. Honeywell, supplier of the C919’s avionics and other systems, was also cited as potentially being banned from further exports.

The story has a ring of truth. What better way to damage a growing economic rival than to cripple a flagship aerospace programme — one that could threaten the narrowbody duopoly enjoyed by Boeing and Airbus?

With six Leap-1C-powered C919s conducting flight tests and the indigenous AVIC Commercial Aircraft Engine CJ-1000AX likely years away, the denial of Leap engines would all but destroy the nascent C919. GE has not, apparently, had any issue obtaining licences in past years.

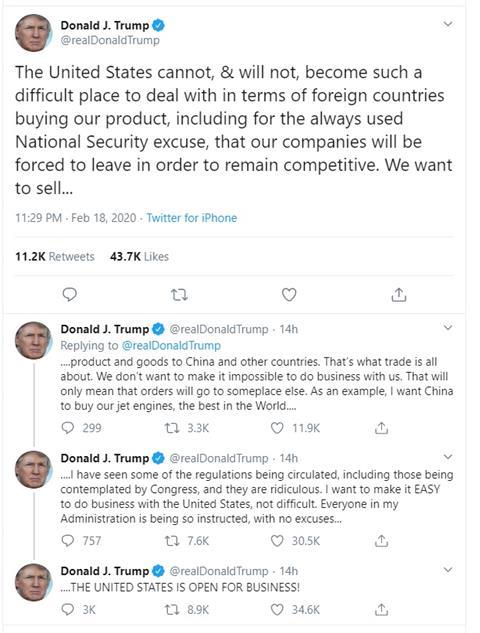

Then, on 18 February, Trump appeared to kybosh the idea of denying export licences in a series of tweets. He contended that the USA should be easy to do business with, and that “I want China to buy our jet engines, the best in the World….”

The supposed rationale of the licence denial is protecting the Leap’s intellectual property. No other issue vexes the Chinese aerospace sector more than the development of jet engines. Washington’s fear, apparently, is reverse engineering.

GE, the joint venture partner of Safran in CFM, has this to say about IP concerns: “GE has provided products and services in the global marketplace for decades. We aggressively protect and defend our intellectual property and work closely with the US government to fulfil our responsibilities and shared security and economic interests.”

Curiously, the Leap and other advanced engines have been in service within China for years. China’s airline sector would not exist without such engines. Cirium fleets data shows that Chinese airlines operate nearly 3,500 aircraft. The vast majority of these are produced by Airbus and Boeing and powered by GE, Rolls-Royce, and Pratt & Whitney engines.

“Reverse engineering of a complex commercial aero-engine is extremely challenging,” says Rob Morris, global head of consultancy at Ascend by Cirium.

“If China wished to understand the architecture of the Leap engine, there are already almost 100 737 Max aircraft with Leap engines installed with airlines in China, plus further Leap-powered A320 aircraft. These will all require maintenance at some point, which will often be in shops within China. However, part of the key to these engines is the manufacturing technologies inherent in the engine components which GE and its supply chain have perfected over many years. This cannot be reverse engineered.”

He points out that Ascend forecasts deliveries of about 1,300 C919s through 2038, making this a huge market for CFM and other suppliers.

A source at one of the top three engine makers notes that even were Beijing’s engineers to get their hands on the detailed blueprints of an engine, they would find it packed with references to esoteric proprietary processes, making it challenging for a copycat to develop a complete picture.

That said, Beijing is not beyond acquiring advanced knowledge through alternative means. Periodically charges have emerged about Chinese spying in the aerospace sector. One area of clear interest is jet engine technology. This issue is separate, however, from reverse engineering.

The Wall Street Journal story and Trump’s tweets have emerged amid several other story threads related to China’s aviation sector. In mid-January Washington and Beijing signed a trade agreement that could greatly benefit Boeing and the broader US aerospace sector in the next 24 months, with Beijing committed to buying $77.7 billion worth of US manufactured goods during a two-year period.

The deal, announced before the coronavirus crisis gripped China, created hopes that China’s de facto boycott of US aircraft since 2017 would be lifted.

And while killing the C919 would ostensibly be long-term positive for Airbus and Boeing, the Seattle manufacturer’s top priority globally and in China is the return to service the grounded 737 Max. The recertification of the 737 Max in China could suffer were any Leap-1C sales ban to emerge.

Moreover, companies such as CFM, Honeywell and other USA suppliers would also fail to recoup their investment in the C919 programme, potentially impacting US jobs.

“If they go forward with this, it will demonstrate a complete misunderstanding of how aircraft, and indeed technology, works,” says Teal Group analyst Richard Aboulafia.

“Either China has access to these engines for their own aircraft and for imported aircraft or not. The idea of stopping them from buying both seems impractical, so the upshot would be to cut them off from all aircraft imports, and therefore to eliminate the biggest single export market for Airbus and Boeing,” he adds.