UK investigators have concluded that a catalogue of administrative and procedural errors contributed to the death of a member of the public after the downwash from a search and rescue helicopter blew them over as it came in to land at a Plymouth hospital.

Detailing the issues in its final report into the 4 March 2022 incident, the UK Air Accidents Investigation Branch (AAIB) says there was confusion among all parties as to who was responsible – if at all – for clearing the helicopter landing site at Derriford Hospital and, crucially, the surrounding area.

Operated by Bristow Helicopters on behalf of the UK Maritime and Coastguard Agency, the crew of the Newquay airport-based Sikorsky S-92 (G-MCGY) had been tasked to extract a hypothermic casualty from a river valley near Tintagel, Cornwall.

Having winched the casualty out, a decision was taken to transfer the patient to hospital in the S-92 – a journey of around 10-12min rather than the alternative road transfer that would take several hours.

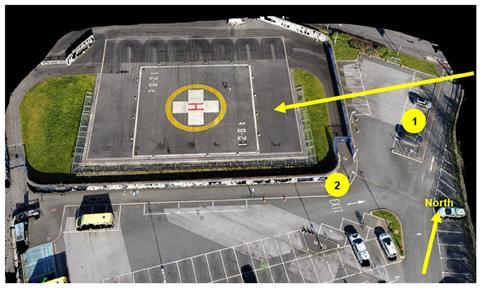

During their transit to Derriford Hospital – located to the north of Plymouth – the S-92’s flightcrew settled on a westerly approach to the facility’s helicopter landing site (HLS) to take advantage of a slight northwesterly wind.

However, the pilots noted that with the wind direction “the downwash would be blown towards the car park that bordered the south and east side of the HLS”.

Both flightcrew members were highly experienced, having previously flown the Westland Sea King in the Royal Navy.

Due to the nature of the approach – involving a “lateral change of line from over the public road to slide forward and left to the HLS” – only the co-pilot “would be visual with the car parks” in its later stages. As such, he was selected to fly the approach and landing.

As the S-92 passed through 1,100ft above ground level, the helicopter commander warned that the downwash “will be going over the car park to the left” – known as car park B – and said that a go-around should be performed if the co-pilot thought it necessary.

According to the aircraft’s operations manual, maximum downwash from the S-92 is around 50kt (92km/h) and occurs around 100ft below the helicopter – in this case, around 25s before landing.

Once below 80kt (150km/h), the right-hand door of the S-92 was opened by the winch operator who reported that the HLS was clear.

While an individual was spotted in the car park overflown by the helicopter, the co-pilot “also believed he saw two people… at the southwestern end of the HLS wall, walking in an easterly direction along the footpath”.

In addtion, hospital CCTV footage also showed two other individuals walking along the southern wall of the HLS who then stopped, at the gap in the wall’s southeastern corner, to watch the S-92 approach.

“Twelve seconds later they were both blown over with one of them sustaining a serious head injury,” says the report. Although the individual with the head injury was treated immediately by paramedics and transferred to the hospital’s emergency department within 14min they died later that day.

In the immediate aftermath of the incident, Derriford Hospital banned helicopters with a maximum take-off weight above 5t – the S-92 tips the scales at around 12t – from using the HLS. Additional restrictions on access to the car park were also imposed.

Post-incident interviews with the S-92’s crew revealed confusion over who, if anyone, was responsible for controlling access to the HLS and the surrounding car parks and roads, or if and when risk assessments had been conducted.

“[The co-pilot] added that he had an expectation that every hospital had undertaken a risk assessment of their HLS and would have identified the appropriate third-party mitigations,” the investigation says.

But it transpired that no-one working at the hospital in risk-assessment roles had any experience of helicopter operations. The designers of the HLS, which opened in 2015, also lacked direct aviation experience, the report says.

Guidance published by the Department of Health in 2008 said a downwash zone of at least 30m (100ft) should be established around helipads for light helicopters “which should be kept clear of people, parked cars and buildings”. A larger downwash zone of an unspecified size was required for larger helicopters, it adds.

The AAIB says the design of the Derriford HLS “appears to conform” to these regulations.

Subsequent advice from the UK Civil Aviation Authority (CAA), which was not retrospectively applicable, specified an exclusion zone for heavier helicopters of 50-65m. AAIB analysis shows that most of car park B is within the downwash zone for a large helicopter.

Risk assessments conducted ahead of the HLS’s construction only identified the risk of downwash “causing harm to members of the public” within the confines of the landing site itself. As a result “all the mitigations focused on limiting access to this space”, says the report.

A document issued by the hospital in 2015 advised that helicopter operators should arrive and depart by designated flightpaths; however, Bristow treated this as “advisory” as meteorological or performance considerations could dictate a different approach. This divergence in policy was not communicated to the hospital, however.

Other helicopter operators using the HLS also used different flightpaths, the report notes, which in some cases had similarly not been shared with the hospital.

A separate operations document published by the hospital in 2015 also detailed that its emergency response team was not responsible for managing people outside the HLS boundary.

“[Bristow] was sent a copy of this in July 2017 but they could not find it at their headquarters or their Newquay base. Other operators that use the HLS at DH had not seen this document,” the investigation adds.

The hospital trust’s standard operating procedures manual for the HLS, issued in 2020, also “did not specify any required actions during a helicopter arrival with respect to pedestrians or vehicles in any hospital car park or on the road outside the HLS boundary”, the inquiry states.

As a result of its inquiry, the AAIB has issued nine safety recommendations for several organisations, including the CAA, National Health Service bodies and others, focussed on improving guidance and assessment of downwash risks. Specific helicopter training should also be introduced for landing site managers, it adds, and a ‘live’ database of HLSs established.